Silence of suicide

There is no closure in suicide.

It is not an infectious disease; it is not a criminal.

There is nothing to hate when everything is over. There is no way to get revenge.

There is only the face of a loved one who dealt with pain to such a degree that there is no way to put it into words.

It is a pain so profound that it seems like it will last forever. But life is a collection of temporary things; we are always growing, always adapting, always moving forward in the lives we create for ourselves. There is always hope of a better tomorrow.

Pain that lasts forever

Story by Colton Johnson, feature editor

Shara McRae, Ashlie McRae’s older sister, holds Ashlie’s picture and necklace while showing a tattoo inspired by one of Ashlie’s drawings. Ashlie passed away on May 28, 2016.

“Shara, it’s your sister.”

Her throat clenched up on itself, and her stomach dropped.

“He either beat her or she’s dead,” she thought as she started the car.

But she couldn’t be dead. It was impossible.

It was impossible for the flashing blue and red lights to be there, in her own front yard, illuminating the solemn faces. It was impossible for her sister, who she had just seen hours earlier, full of life, to be reduced to silence. It was impossible. It was impossible.

But it wasn’t impossible. It was her new reality, and it altered every photo that would someday be taken. Every memory that she would make. Every day, she would remember that there was something missing.

Ashlie McRae took her own life on May 28, 2016. For her sister, 24-year-old Shara McRae, this was the day when the world stopped spinning. Suicide is the second leading cause of death among teens, leaving many families like Shara’s to deal with the aftermath.

“It’s been horrible,” McRae said. “It’s not like a car accident. It’s not something that you can ever have closure about.”

For McRae, life turned into a perpetual state of anger–of wondering why. It consumed her, and she was left with nowhere to project the inconsolable storm of confusion.

“You would think that death would be so easy, but it’s so complicated,” McRae said. “It comes with so much grief and so many different emotions, and I don’t feel like there’s any justice in it.”

According to Shara, Ashlie had found herself in a bad relationship that made her feel worthless. She turned into someone she wasn’t. After Ashlie took her life, McRae found herself frozen, trying to find closure in a world that never seems to take a break from everyday life. While her axis may have stopped spinning, the world around her did not.

“I think the hardest part about it was going back to my everyday life. Driving home, I was looking around, and it’s so weird because everyone is going on in the world. They move on without you whether you can move on or not, whether you’re ready to or not,” McRae said. “They are fine, and you’re dying on the inside. I literally feel like part of myself died with her.”

“I think the hardest part about it was going back to my everyday life. Driving home, I was looking around, and it’s so weird because everyone is going on in the world. They move on without you whether you can move on or not, whether you’re ready to or not,” McRae said. “They are fine, and you’re dying on the inside. I literally feel like part of myself died with her.”

McRae’s confusion for Ashlie’s decision forced her take a step back to reevaluate–to overthink. Before, when the idea of suicide affecting someone she loved was impossible, she didn’t give it a second thought. Now, she could lose anyone.

“I never would’ve thought this could happen in a million years, and after this, it could be anybody, so I’m worried about everybody. Me and my sister were just starting to really get close,” McRae said. “She was very alive. She was such a warrior to me. She had that fire in her.”

In the wake of the tragedy, McRae was soon confronted with the question of: What now? She was left trying to figure out how to begin a new chapter without her sister, and so she separated herself from the situation. She left it in the back of her mind, for a later date that she always seemed to push farther back on her calendar.

“I went to therapy for a bit and so did my mom, and they put me on medicine, but I didn’t like it. I know it’s not healthy, but I’m scared to deal with it, so I ignore it. I’m scared to go through that because I know you have stages,” McRae said. “There’s a lot of things you have to think about. Like she’s not gonna be there for

your wedding. She’s not gonna be there for a graduation. I’m not gonna remember her smell. If I could see her again, I wouldn’t say anything. I would just hold her. There’s nothing I could say. I would just have to hold her. To feel her and smell her again.”

Suicide, it seems, has a tendency to run in families. Years ago, Shara tried to kill herself in the same way that Ashlie did. Shara was lucky enough to have someone there to show her how much she was worth.

“I don’t even remember the reason why.,” McRae said. “But I didn’t do it. When I was going through that, my cousin, Katie, busted down the bathroom door and grabbed me by the ponytail and dragged me down the hall and beat the dog crap out of me. She was just telling me how much I’m needed. I had someone bring me back to my senses, and I don’t even know why I was in that thought. I have a lot of regret that I tried doing that.”

After this incident, Shara began to notice that everyone goes through trials everyday, and that suicidal tendencies aren’t confined to trying to take your own life.

“It changed my mindset on a lot of things like how I approach people with their daily struggles because everybody is going through struggles,” McRae said. “Maybe not everyone wants to kill themselves, but some people self harm, some people drink or some people overeat. There’s all kinds of different ways people deal with their own problems.”

After her own suicide attempt and after seeing the reaction to Ashlie’s death, McRae soon came to realize that suicide is not something people are openly willing to discuss. It is a conversation kept in quiet murmurs.

“A lot of people are very hush hush about it,” McRae said. “I know a lot of people can’t talk about it because they’ve never been through it or they don’t understand it.”

“A lot of people are very hush hush about it,” McRae said. “I know a lot of people can’t talk about it because they’ve never been through it or they don’t understand it.”

With lack of understanding comes ignorance. This culture has made the idea of suicide out to be a joke, and Shara has witnessed it first hand.

“I have friends who come up to me and say things like ‘Oh I could just hang myself,’ and I just think, ‘How could you say that?’” McRae said. “They aren’t thinking about other people’s feelings and emotions and what they’ve been through, but you can’t get upset with people because no one is going to know everything that you’ve been through. I would rather people watch what they say and how they say it.”

Ultimately, suicide is a conversation that needs to be talked about respectfully, for all of the people like Shara who are left in the wake of the tragedy. It cannot be a topic that is pushed under the rug, and for those who are in a dark place in their life, it is important to know that there are indeed better things to come.

“Always talk to someone about it. Not everyone is going to ask for help though, and to those people, there’s a light that never goes out. There’s always something better around the corner. It’s always going to be better. It’s never going to be as bad as you think it will,” McRae said. “I wish everyone could go through the loss of someone that is close to them without going through that loss. I wish they could feel actually having to deal with that.”

A million reasons to live

Story by Colton Johnson, feature editor

Our society tries to convince fretting minds to live in the moment. We idolize the future, sure. We try to plan our entire lives, but we always try to bring ourselves back to the present out of fear of watching it all go by.

Well, people do that for the good times–the moments that they feel happy.

But for Samantha Walker, there were no more of these good times to come back to. There were no ways of escape. There were no promises of hope or of better things to come. There was just the present–a world that was folding up on her.

She made the decision Oct. 23, 2016, that it wasn’t worth it anymore. The suffering outweighed any good memory or any light her future held. She was stuck, and at the time the only way out seemed to be through the pills in the little orange bottle.

It was easier that way.

“In that moment, I wasn’t thinking about anything but the pain I was feeling,” Samantha said. “The thought hadn’t occurred to me that I might actually be hurting someone.”

Samantha did not intend on surviving. She would come to find out that her decision left a far greater effect than she believed it would; especially for her twin sister, senior Savannah Walker.

“When I got in the car Samantha was out of it. The pills were already in her system. She couldn’t even look at me,” Savannah said. “She’s my twin sister. I don’t know if you’ve ever seen something flash before your eyes, but my heart just broke. It was probably the saddest moment of my life.”

When Savannah saw her sister sitting there in the car, she saw her past self as a freshman–her broken self who had tried to overdose the same way as her sister now was. Feelings of feeling unwanted and unloved had plagued Savannah years before just as it had taken control of Samantha.

“I was mad because she did it, but at the same time I understood. It made it worse because she knew how she felt when I tried it. She knew how bad it was,” Savannah said. “I know in those moments that you don’t think about what anyone else really thinks, but I felt like we weren’t enough. I felt like I wasn’t enough.”

Samantha was in admitted into (name) hospital and stayed in a medically induced coma for three days.

“I remember when we were sitting in the waiting room and they were getting ready to airlift her to Little Rock,” Savannah said. “My mom just burst into tears and kept saying, ‘I can’t lose her.’”

Once she woke up from her coma, she was sent to Riverview Behavioral Center, where she stayed for a week, and while help was offered, it didn’t seem to be the help she was in need of.

“I had to go to group therapy everyday and speak with different doctors about what I did and why I did it,” Samantha said. “I was diagnosed with major depressive disorder, and they put me on medication to help with it–but it didn’t really help.”

The silence did not build her up either. The flood gates of support did not seem to open for Samantha as they had for others.

“The topic of suicide comes up and everyone gets quiet. You’re not supposed to talk about it. You’re not supposed to acknowledge it,” Savannah said. “She wasn’t a popular kid. It was upsetting because whenever Mayten’s injury happened, people rallied around him and everyone wore yellow, and that is great for him, but no one really thought to do anything for her. I had a couple of friends try to make a t-shirt for suicide awareness, but it didn’t go anywhere. No one really did anything extraordinary.”

Suicide is not a comfortable topic to discus for many people. It rests in a grey area with so many unanswered questions. There is the argument of morals and speculation questioning the “real” reasons that people do it.

“People think it’s for attention,” Savannah said. “My sister was in a bed for three days asleep. She was on a ventilator. She couldn’t breathe on her own. I don’t think that was for attention.”

So, how do we break this stereotype that suicide is simply a selfish act for people seeking attention? We talk about it. We open our arms to people who are hurting.

“The school has a bullying and suicide prevention workshop at the beginning of the year, and it’s like you hear about it but you don’t have to go,” Savannah said. “I think they could hold an assembly that we are required to go to that just talks about it–at least once. They need to do it for everyone so people know they aren’t alone and they have somewhere to go.”

Suicide is not a topic that this school is unfamiliar with, and yet it is something that is brushed under the rug when it happens. It cannot be ignored anymore, and it is time to talk about it now. We cannot put it off, and we cannot just talk about it when it happens. We must talk about it in order to prevent it from happening.

“We’ve had so many people at this school attempt or actually done it,” Savannah said. “When you have so many people at this school who have attempted to do it, it’s a topic that needs to be talked about.”

Pain of this magnitude may seem like it will never end, but nearly everything in life is temporary. Anyone who is or has considered suicide must remember that things will eventually pass. You will look back someday and say that you made it just as Savannah and Samantha have.

“Things get better,” Samantha said. “A couple months ago I didn’t see a reason for living. Now I have a million reasons to [live]. I live with my cousin and his wife in New Mexico now. They have twin one-year-olds, and they are one of my reasons for living. I want to be able to see them grow up.”

Help is within reach

Story by Anna Cannon, editor in chief

In 2003, suicide was the third leading cause of death of teenagers ages 10-24. As of now, it is the second leading cause of death. There isn’t an exact reason for the increase in suicide, but there has been an increase in efforts to stop it. Still, the subject remains taboo, and as a result, a lot of misunderstanding surrounds it.

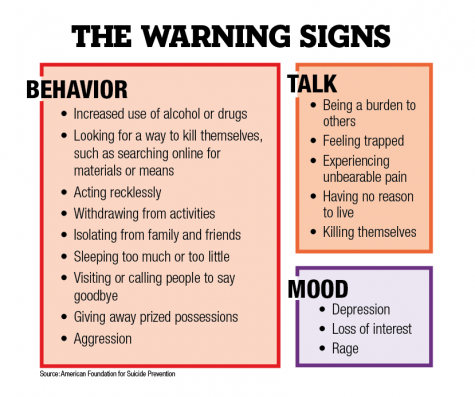

There is no definite cause of suicide. Unlike a physical illness, there’s no specific virus or germ that can be blamed, but common denominators can help us understand better. Most suicide victims suffer from Major Depressive Disorder, better known as depression. Many victims also had biological differences in their brains. According to a study by researchers at the New York State Psychiatric Institute, many have an excess of serotonin receptors. An excess of serotonin (a neurotransmitter) can lead to impulsive behavior, faulty decision making and an increased risk of depression. Because we are born with all the serotonin receptors we’ll ever have, this is evidence that some people may be born with a biological predisposition toward suicide, and accounts for the fact that suicide often runs in families.

Depression is the leading cause of teen suicide, but there are other risk factors to watch for. Traumatic life events, such as the death of a friend or family member, a serious breakup, or mental, physical or emotional abuse can be the catalyst for suicidal thoughts or actions. Substance abuse, anxiety disorders or other mental health problems–such as bipolar disorder, schizophrenia or eating disorders–greatly increase a teen’s risk of suicide.

Depression is the leading cause of teen suicide, but there are other risk factors to watch for. Traumatic life events, such as the death of a friend or family member, a serious breakup, or mental, physical or emotional abuse can be the catalyst for suicidal thoughts or actions. Substance abuse, anxiety disorders or other mental health problems–such as bipolar disorder, schizophrenia or eating disorders–greatly increase a teen’s risk of suicide.

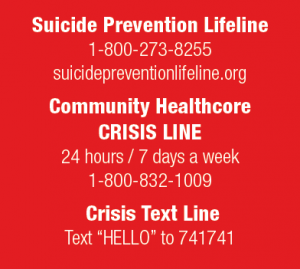

If you’re suicidal, the first step toward getting help is telling others. Talking to your best friend may be helpful, but unless they’re a trained mental health professional, you’re going to need more. The school counseling center, located near the south exit of the math and science building, is available to anyone who might be struggling with thoughts of suicide. From there, the counselors can put you in touch with trained psychiatrists and therapists. Helping a suicidal person is a team effort.

There are several online resources that can be used to help diagnose or cope with mental illness. Just searching “depression test” or “anxiety test” will provide a range of options for self diagnosis. There are online helplines for practically every mental illness, and resources for helping to manage grief, stress and other factors that could contribute to suicidal thoughts or actions.

Self diagnosis and treatment can be helpful in the short run, but the best way to get help is to be diagnosed by a professional. Your general practitioner can recommend psychiatrists, therapists and counselors in your area. Healthcare databases can do this as well. If you want faith-based treatment, talk to your religious leader; they can often recommend a faith-based counselor.

But don’t be fooled into thinking that mental illness can be “cured;” many people with a mental illness will struggle with it their whole lives. Our minds are so much more complex than any other part of our bodies, so treating the mind must be more complex as well. There’s no magic pill that will make all of your problems go away, nor is there a quick counseling session that will make you feel like new. Recovery takes time and effort, and mental health professionals can only help their patients as much as they want to be helped.

There’s no formula for suicide; there’s no rule for what can make a person take his own life. Everyone responds to situations differently, and everyone’s mind works in its own unique way. Some people have the mental strength and external support system to navigate traumatic life events without ever considering suicide. Others may not have the strength or support to survive the same circumstances. Just because you believe that you would have been okay in someone else’s situation doesn’t mean that they were weak, or that their struggle wasn’t valid.

If someone you know is struggling with suicide, don’t keep quiet. Tell an adult, call a helpline or talk to a counselor if one is available. If the situation is bad enough, take them to an emergency room. Don’t leave them alone, and don’t try to keep it secret.

Suicide isn’t something that we can keep quiet about. The second leading cause of death among young people can’t be brushed under the rug.

No one should have to suffer in silence because they are afraid of being judged or not taken seriously. Don’t accept for an instant that someone is just doing it, “for attention.” Suicide deserves our attention, as do the people who suffer under its grip.

[email protected]

Kayleigh Moreland is a senior and the yearbook photo editor for the 2016-2017 school year. During her free time,...