Read between the lines

Billy Collins’ work is accessible for everyone

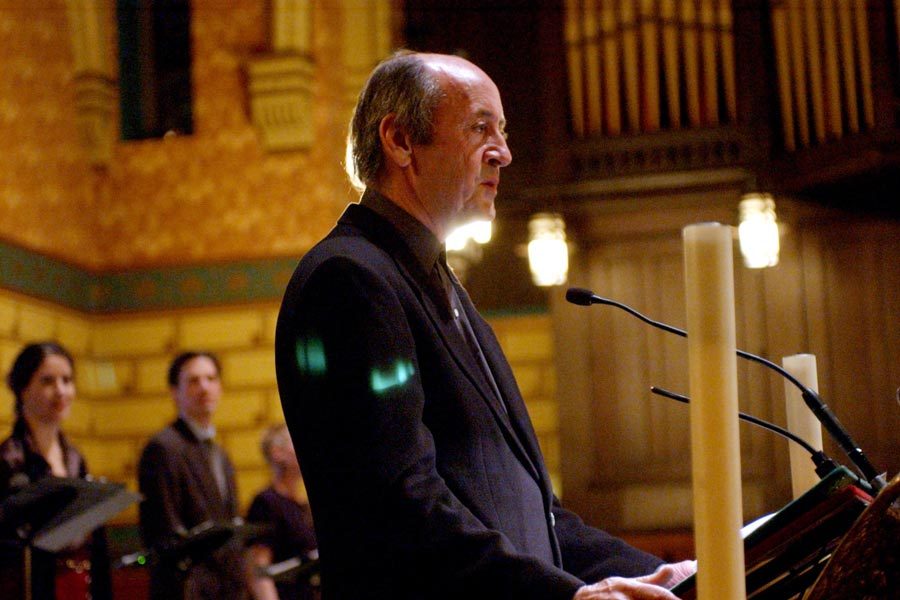

Poet Laureate of the United States Billy Collins speaks at the 90th anniversary celebration of Poetry magazine at St. James Episcopal Cathedral in Chicago, Illinois. Photo by Charles Cherney, via MCT Campus.

April 4, 2017

You might not read poetry. You might get lost around all of its corners, too busy deciphering abstract images and conventions of grammar you haven’t seen. Poetry has often been folded up and tossed away like the receipt of everyday transactions, but some stands the test of time. The work of U.S. Poet Laureate Billy Collins is meaningful, both in its wit and its volume

Collins offers a lot in his poetry, namely a conversational tone and incredible warmth. His poetry is easy to read and understand, making it greatly accessible to a large population of readers. Although his poems are easy to grasp, they are incredibly layered, being much deeper than they appear on the surface.

Collins writes in his “The Death of Allegory,”

“I am wondering what became of all those tall abstractions

that used to pose, robed and statuesque, in paintings

and parade about on the pages of the Renaissance

displaying their capital letters like license plates…”

Speaking on personal behalf, this poem reminds me of the things we have lost in language. The meaning of our words have lost their impact and we, as a society, have lost the ability to articulate ourselves like those in the past were able to.

In this poem, the elements of romanticism and modernism are inextricably fused. He was greatly influenced by the Victorian era poets, such as Thomas Hardy, Lord Alfred Tennyson and Robert Peters. In his early childhood, he was recited verse by his mother, who stopped working as a nurse to care for him. In his middle school years, he wrote poems that were dark and Gothic.

Collins is also an advocate of education of the arts. During his time as Poet Laureate, he instituted the Poetry 180 program, sending a poem to schools for everyday of the school year. The program is now online and all of the poems are free of charge.

U.S. Poet Laureates are not hired to write poetry, unlike their British counterparts, but a famous poem, “The Names,” was commissioned by the Librarian of Congress to commemorate the 9/11 attacks. Collins initially refused to read the poem, refusing to capitalize off of the terrorist attacks.

An excerpt from “The Names:”

“…In the morning, I walked out barefoot

Among thousands of flowers

Heavy with dew like the eyes of tears,

And each had a name –

Fiori inscribed on a yellow petal

Then Gonzalez and Han, Ishikawa and Jenkins…”

In this poem, the names of people appear out of everyday objects and the emotional intensity grows with each passing reference. It touches me each time I read it. By assigning metaphorical value to a few names, the appreciation amounts more and more and makes me think of all the people whose life pass us by and we never to get to give thanks to, or for all the people who we pass in the hall and become entranced with the idea of.

His poetry is never encumbering or trife. His works have emotional intensity, even when he is describing to the reader quaint environments: the land after rain, a child’s birthday party, the first night after death, and others. His original mystique has won for him numerous awards, including the Oscar Blumenthal Prize, the Bess Hokin Prize, the Frederick Bock Prize, the Levinson Prize and “Poetry Magazine’s” “1994 Poet of the Year.”

I relate to Collins mostly when he writes of an experience with his mother. This poem, “The Lanyard,” is a beautiful rendering of the feeling that you cannot reciprocate a mother’s love for her child.

Collins writes,

“’And here,’ I said, ‘is the lanyard I made at camp.’

‘And here,’ I wish to say to her now,

‘is a smaller gift. Not the archaic truth,

that you can never repay your mother,

but the rueful admission that when she took the two-toned lanyard from my hands,

I was as sure as a boy could be

that this useless worthless thing I wove out of boredom

would be enough to make us even.’”

A beautiful outlook on motherly love, I feel close to Collins’ work and the way he narrates this poem, ending it with an ultimatum and meaningfully understated–the type that speaks for itself.

Poems by Collins say little but speak a lot. Other contemporary poets that might appeal to readers of Collins’ include but are not limited to: Safiya Sinclair, Rupi Kaur, Mary Oliver, Charles Simic, and Marie Howe.

Collins humbly narrates the human condition, made readily accessible and possible to appreciate without looking down in confusion. His poems beckon us to wonder, and we learn to respect without abstaining, to collide without withholding and to feel without resisting.